ONLINE NEWS: SEAGRASS, NOT SEAWEED: MALAYSIA'S MARINE SCIENCE GROUP LEADS CHARGE IN CLIMATE-RESILIENT SEAGRASS SANCTUARY

THIS WEEK IN ASIA

Ushar Daniele

Published: 2:00pm, 9 Oct, 2022

Middle Bank sanctuary, just a few kilometres away from the port of Penang, has been earmarked as an area of study of climate change resilience. Photo: Cemacs

Seagrass, less commonly known than its aquatic cousin seaweed, is often overlooked in providing a sustainable natural sanctuary for marine ecosystems. Like many other ecosystems, seagrass meadows are at risk of disappearing from the oceans because of climate change.

Enter Universiti Sains Malaysia’s (USM) Centre for Marine Science and Coastal Studies (Cemacs) in Penang that is leading efforts to establish a new marine sanctuary for seagrass.

Cemacs is working to determine the extent and impact of global warming and rising sea levels on seagrass meadows in Middle Bank, Penang, in a 30-year study. Findings are shared with public and private stakeholders and aim to promote climate change adaptation and resilience, with marine and coastal ecosystems as integral parts of future solutions.

With sea levels projected to increase by 1-5 metres by 2100, Cemacs is exploring methods to protect seagrass and the marine life that call it home.

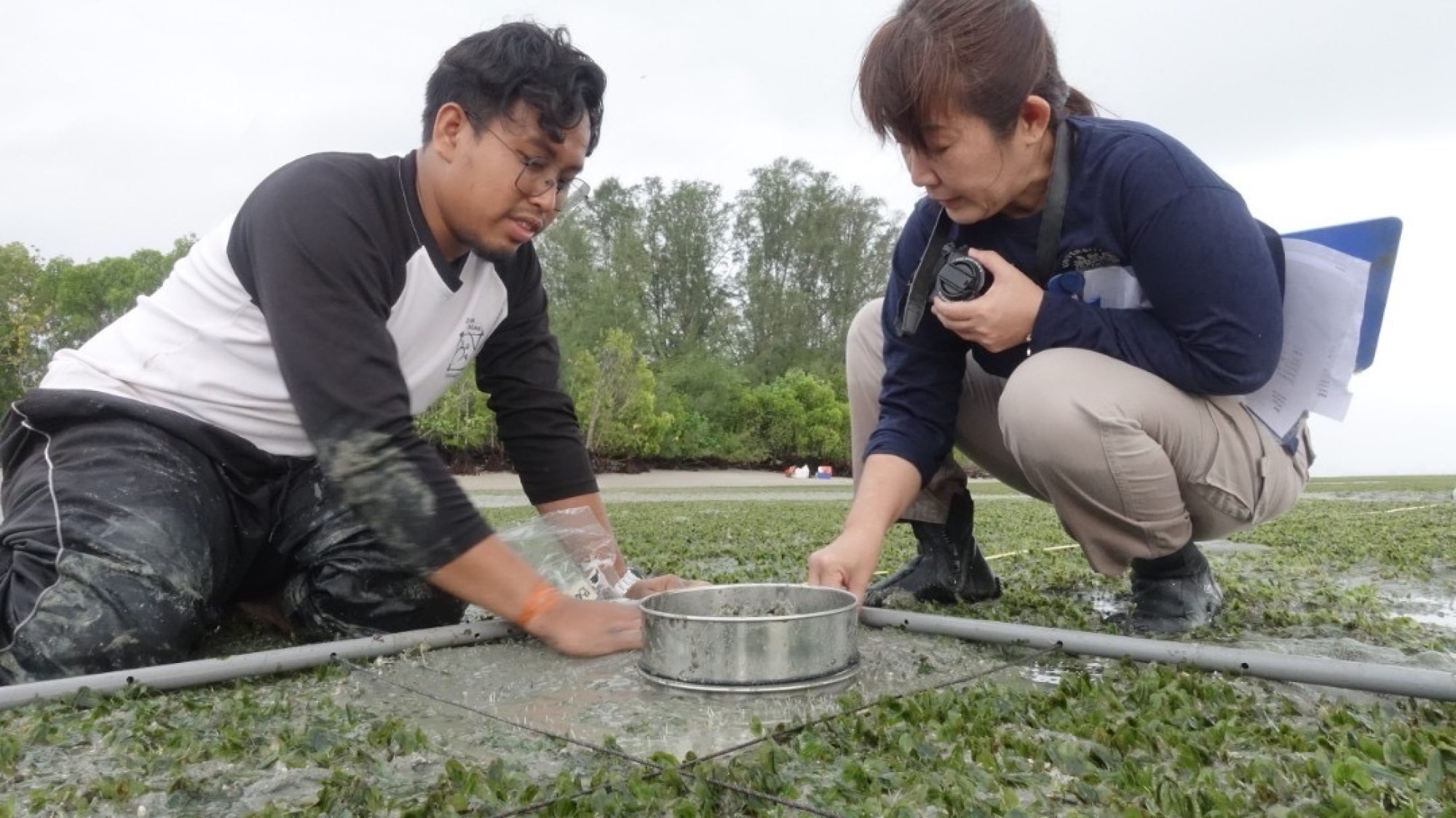

Cemacs’ director Aileen Tan (right) said Cemacs’ 30-year project is looking at ways to protect the seagrass ecosystem and marine life in it. Photo: Cemacs

The Penang state government has created a multi-agency committee to support the planning and establishment of the marine sanctuary.

Cemacs’ director Aileen Tan said the establishment of a new marine sanctuary – an urban marine sanctuary for climate resilience – could be a model in other parts of the country and the region.

“Seagrass beds are one of the most productive marine ecosystems to sustain fisheries resources and are also biodiversity hotspots because they act as a nursery, refuge and feeding ground for a variety of species of fish and invertebrates,” Tan said.

“Rising sea levels may adversely impact seagrass communities due to increased water depth, which reduces light, alter currents causing erosion and increased turbidity,” she added.

Seagrass grows in abundance, creating a green meadow in shallow waters often surrounding mangroves, coral reefs, shoals and semi-enclosed lagoons. It sustains fisheries by functioning as a nursery, refuge and feeding ground for fish and invertebrates. Aquatic mammals like dugongs, turtles and seahorse also call these meadows home.

Seagrass meadows also reduce the impact of storms, support coastal communities and filter out pathogens, bacteria and pollution. Such meadows cover just some 0.1 per cent of the ocean floor but store up to 18 per cent of the world’s oceanic carbon.

According to a 2020 UN Environment Programme (UNEP) report titled Out of the Blue: The Value of Seagrasses to the Environment and to People, seagrass meadows are among the most common coastal habitats on the planet, covering over 30,000km² of the ocean in more than 150 countries.

Seagrass beds are among the most productive ecosystems in the world. Such meadows cover just some 0.1 per cent of the ocean floor but store up to 18 per cent of the world’s oceanic carbon. Photo: AFP

UNEP estimates that 7 per cent of such habitats are lost every year and nearly 30 per cent of known seagrass areas across the globe have been lost since the late 19th century. At least 22 of the world’s 72 seagrass species are also on the decline.

Since 2019, the USM team has conducted research on seagrass and biodiversity in the Middle Bank area, just 3.5km away from the Port of Penang, the third busiest harbour in Malaysia in terms of cargo volume and the country’s busiest port-of-call for cruise ships.

Studies have shown that temperature changes affect seagrass distribution, sexual reproduction patterns, growth rates, metabolism and carbon balance. When temperatures exceed the threshold for a seagrass species, entire meadows may die.

Rising temperatures can also accelerate the growth of competing algae and similar species, which can outgrow seagrass and deprive them of sunlight.

In 2014, Cemacs conducted a study of gastropods and sea cucumbers that thrive in seagrass beds in the Merambong Shoal in Johor and in Gazumbo Island in the northern region of Peninsular Malaysia and found that the growth of seagrass strengthened biodiversity.

Such findings go a long way in promoting the protection of the seagrass meadow just a few kilometres away from one of Malaysia’s busiest ports.

Balancing economic growth and the environment

Tan and her team continue to face a balancing act in convincing stakeholders – including the government, local agencies, non-governmental organisations and the public – to commit to transforming a relatively valuable waterfront to a marine sanctuary.

Penang was Malaysia’s fastest growing economy in 2021, with growth of 5.8 per cent. Services accounted for 47 per cent of its gross domestic product growth while manufacturing contributed 47.3 per cent.

Penang was Malaysia’s fastest growing economy in 2021, with growth of 5.8 per cent. Photo: Shutterstock

Penang state executive councillor and chairman of the Welfare, Caring Society and Environment Phee Boon Poh said the Middle Bank was initially gazetted for development in 2008 but the state later learned that the seagrass meadow in Middle Bank was one of the two main meadows in the northern region of Peninsular Malaysia.

“Penang has one of the biggest meadows and we had to do something about it and through studies. We could convert it into a marine sanctuary that not only protects the ecosystem in the area but also promotes food security,” Phee said.

While urban development is reclaiming the shorelines of Penang, Phee said that the government has made efforts to build artificial reefs and introduce technology into this marine sanctuary.

According to the Penang state exco for Environment, Welfare and Caring Society, fishermen around the seagrass sanctuary fear that conservation efforts would take a toil on their livelihood, a concern that the government is addressing through community engagement and providing additional support such as education to the coastal community.

“Once we are ready, we have a few thousand fish farmers who are supposed to contribute at least 1,000 fishes, not less than four inches (long), into the sanctuary yearly,” Phee said.

The government also plans to introduce open and closed fishing seasons “to a certain extent” around the marine sanctuary. Closed seasons address overfishing by allowing fish populations to grow.

The sanctuary will adopt categorisations from Swiss-based global nature conservation group, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, in establishing the marine sanctuary. The protected area will be managed through conservation and management intervention.

“This will provide flexible management strategies and options in buffer zones and these protected areas are more acceptable to local communities and other stakeholders.”

This story was supported by the Earth Journalism Network and Climate Tracker.

- Created on .

- Hits: 1280